When we emi/immigrated 27 years ago it was accomplished with some considerable naivete and not a little starry-eyed idealism, but we made it; here we are. The idea was to “be artists”… yeah, what can I say, we were in our 20’s. We did plan our arrival carefully, though. We had sold our car and virtually everything else we owned, reducing our possessions to books, heirlooms, and personally treasured items which we left in storage with family,

and two backpacks in which we had all the clothing we kept, a couple of towels, toiletries & etc., books about our destination, some bare essentials for starting out as artists, and our entire worldly fortune in traveler’s checks (just about $3,000, I believe it was). This was long, long before smart phones, tablets, and so on. We knew we would be jetlagged and overwhelmed, so rather than start out immediately on the search for a suitable hostel from which to quest after something more permanent, we had booked a hotel for the first three nights. We didn't buy return tickets; the plan was already never to go back, except to visit. This was it.

The day after we arrived, we had an immense stroke of luck. We’d taken up one of the tour guides and plotted a course of action, and it started with the library. According to the book, the main public library had a large bulletin board where apartments for short-term rental were often to be found. Armed with a dictionary and phrase book, we went about deciphering those ads which weren’t in English, noting down phone numbers and checking locations on our map. We’d been at it a few minutes when a man behind us cleared his throat and said, “Excuse me...”

Yes, the tour guides all warned about being approached by random strangers, especially if said stranger was a fellow non-native, as he was (but he wasn’t a com[ex]patriot; he was from somewhere we’d never even heard of, which was at the time the newest nation on Earth). We have pretty good people-sense though, and his manner was mild and courteous, his smile open, and he seemed a little shy. He explained that he had overheard us discussing apartment listings and had seen our shiny new rings (we got on the plane only a couple of months after our wedding), and that he had a small apartment – part of his own apartment, really – which he rented out and which had recently been vacated. He said he just had a feeling he should give us a chance. That man ended up being our landlord (beginning with a simple three-month-stay agreement) for seven years.

We got here just at the beginning of a massive heat wave, blissfully unaware that local summers aren’t always like that (a rude awakening later, for us desert folk here in this land of perpetugloom and pouring rain). The apartment was what they call an up-and-behind, because it consisted (well, most of it did) of the back half of the top floor. Roofs in that area are flat, and covered in black tar-paper, so under the uncharacteristically beating sun, our home became desperately hot by day. This didn’t cause us a lot of trouble most of the time: we were new here, new on this continent, and there was everything to see. We spent our days walking and walking, looking for opportunities to try to break in as artists or find a job washing dishes or anything at all, reveling in our new surroundings, confusing locals by gawking delightedly at things they no longer noticed or never had. We spent a lot of time in a big park, when we were tired from all the traipsing, and eventually, during some of the leanest times, this would also be where we gathered the bottles to return for the deposits at the night market to buy some spaghetti and if we lucky that day, a bit of sauce to go on it.

We decorated our tiny place with what came our way: a beautiful little ficus vine in a plastic pot which we naively put into the hole in the wall under the mantelpiece where a heater would be if we had one, a placemat we’d picked up of Breugel’s wedding feast, eventually my husband's oil

paintings, and so on. It became downright cozy. Now, when I say this place was small, I mean it was small. It consisted of three rooms: a bedroom in which the sides of the mattress on the floor (our bed) pressed against three walls and barely allowed the door to open all the way; a living room which held a small cold-water basin, a two-person sofa, and a heavy wooden coffee table (about which there will some other time be a very interesting story) and which was so small that one of us had to sit down if the other one wanted to move about the room; and a WC the door of which could not be closed while it was in use because one’s knees were in the way if one sat down on the toilet. The ceiling was falling off in there and in the hallway, chunks of plaster gone to reveal the lathing underneath. Our view was a well of the backs of other apartments floored by the roofs of the shops underneath. It was covered in pigeons and cats and overall not very interesting, but one day a magnificent red harrier hawk dropped suddenly into view and flew low over the roofs, ascending again at the other side to disappear. For showers, and to cook, we descended two flights of very twisty, very steep stairs (down which I once fell, adding a second serious injury to my right knee’s life experiences) into the landlord’s apartment and used the kitchen and shower there.

We were delighted when a cashier at an art store we frequented for our paper, charcoal, pencils, and the like was able to get me an interview at a stable, and suddenly, I had work. Now, although I was working 10-to-12 hour days six days a week, we knew we could stay. Sundays, my day off, we would spend back in that park while the weather lasted, me nursing what I didn’t yet understand was some pretty severe RSI. It got to the point at which I could do my work, but at night and on Sundays my arms would swell and it would be difficult to use my fingers. They felt numb, alien, traitorous. It is what it is.

The landlord was happy with us --- we were quiet and polite and neat, not like the students he’d had in before us, or the divorcee who lounged around the common areas in flimsy clothing, making him uncomfortable. He said we could stay at least another year. The thing was, though, autumn – a phenomenon new to us in this form – was coming in for a landing. Wind storms were picking up, and we discovered why it was a bad idea to have that ficus in that drafty little hole: one day a sudden gust fired it all the way across the room. That apartment was starting to get cold.

The landlord solved this with at first an electric oil-filled radiator that mostly kept us warm enough not to shiver continually if we sat with our hands pressed against it, but after he saw the first electric bill, he replaced it with a small kerosene-burning heater. Many a day for many a year I spent walking and eventually cycling through a bitterly frozen city, teeth chattering, four plastic jugs of kerosene hung about me. We developed a very good relationship with the kerosene vendor, an old-world-type tradesman and craftsman pushing retirement. Once home, we’d funnel the stuff into the heater and spend our days gloriously lukewarm. Nights, not so much. Even had the bedroom been large enough to put the heater in there without setting the bed on fire, we weren’t dumb enough to sleep in a room with something that could essentially morph into a carbon monoxide generator at a moment’s notice (it was only much later that I actually had carbon monoxide poisoning, from an entirely different source, and trust me, it sucks enormous rocks). Thus it was that in winter we would wake up to find our curtains frozen to the windows in spots, the rest of the glass covered – on the inside – with a half centimeter of ice in beautiful quasi-floral patterns.

There was a telephone, but it was in the landlord’s living room and could not be used to dial out. Once a week my grandparents would call us, and I would crouch on the stairs halfway between our apartments, clutching the phone on its long extension cord, and talk to them for a few minutes. If we needed to make a call, we would go outside and around the corner to a pay phone. One that took coins – this was even before those card-reading phone booths that are now also completely defunct, like internet cafes, which we saw rise and fall after our arrival and which one fellow student, when I got my degree in 2009, was literally too young to remember. We had a television we picked up at a thrift store, but no cable, so we were able to watch one or two local stations, poorly. We listened, therefore, to a lot of British radio, becoming ardent fans of such programs as “I’m Sorry, I Haven’t a Clue” and “Just a Minute”.

A room downstairs was also rented out, and of the three people who lived there (not at the same time) while we did, two are still friends of ours.

The front half of that floor of the building belonged to the two women who lived with their children on the middle floor. Our landlord had the bottom floor (not the ground floor; there was a completely separate apartment underneath all of this), thus, and half of the top floor, while the entire middle floor and the other half of the top belonged to the ladies, as we called them. At some point I discovered, I don’t quite remember how, that what I had thought was a door into part of their half

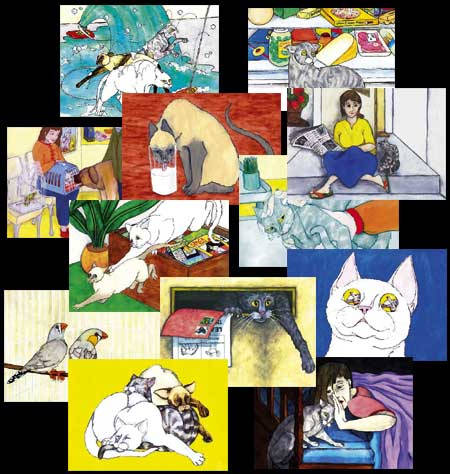

actually led to a very small room being used by the landlord for storage. By stacking his stuff against the wall I was able to free up about half the space – so, an area about 1.5 m² – in which I built a table, and put a kitchen chair I found on the street in there with it. This became my studio, where I learned all about doing art on commission and for exposure (don't!); here are some of the things I painted for other people at that time. These projects were

never published, sadly.

Eventually we did move on from that apartment. Looking back, it’s obvious that it was miserable, squalid, even a health hazard. If we had to consider somewhere like it now we would be appalled. But that isn’t how it was for us then. We were in full-on adventure mode, we had made an enormously bold and potentially disastrous move while in the full flush of newlywedhood, we were proving every day how resourceful we were. The jumpsuits I made us out of Salvation Army blankets, cut and pieced and sewn together with yarn, to stay warm when we were at home, were a point of pride, not a badge of dishonor. Cramming that mattress in there was building a home. It’s the place I first saw snow falling, first saw swans in the air, learned the language. It’s where we lived while we made many of the friends we still have now. It was my base of operations for my first forays into the art world, my first exhibition, my first jobs here (the stable, the cleaning work for the sorry asshole, handing out pub fliers on a busy tourist street, the mushroom farm, and so on).

Do I miss it? No, absolutely not, I’m not crazy. But I do look back on it with a certain nostalgia, and I treasure the memories of that time and place.

Add comment

Comments