Many of the pictures are for sale. To buy or licence any linked photo, just click on it! If you want one that isn't linked, drop me a line.

It’s difficult to know how to begin. I want to talk about bees in my garden but to do that I need to talk about bees – all bees. And to do THAT I need to talk about humanity’s increasing distance, in almost all places, from nature. We live in a world where the prevailing powers – the Industrialized Cities – react to the things our

parasitic species is doing to the world by trying to REPLACE nature, to AMEND it, to DO WITHOUT it, and that is as great a travesty of justice as ever there could be. I’m already in danger of branching off into what we’re doing to the oceans, the very air itself… but I won’t. I will talk about bees.

We know that bees and other pollinators, of which there are a great many, are essential to the very state of life on Earth as we know it. Almost every plant we depend upon, and which by extension the animals we eat and keep as pets rely upon, depends upon pollinators. We KNOW we’re killing them off with pesticides and human-induced climate change and pollution and incompetent husbandry and forcing them into smaller and smaller, less and less natural environments. We know how important that is and how incredibly on the edge of total annihilation our very own habitat is because of this and what are we doing about it?

Are we trying to rehabilitate our world? Are we finding ways to bring down the levels of poison in our air and water, trying to decrease the man-made wastelands of concrete and asphalt and literal garbage spreading like pus from seething wounds across the whole surface of this, the only world we’ve bothered to know? We are not. Sure, here and there someone like me is trying, is creating a tiny oasis against all odds in the middle of a city, and very occasionally someone with more reach – a corporation, a small government, a collective – is making a move here and there to plant up the sides of buildings, re-wild a few dust bowls which once were monoculture croplands where once the real life of the planet thrived, to clean a small patch of water. But it’s a losing battle because the collective will of the Great Moneyed Predatory Powers which want nothing but to use, use, use until everything is gone are taking other routes.

Pollinators on the decline? Simple, they say: REPLACE them with man-made robotic copies, things of metal and silicone whose “hives” will churn through electricity and therefor water and the very sustainability of our world like bitcoin farms, and will fall from the air like the real bees are doing now when we falter and our structures collapse -as is obviously imminent within a generation

Photo: Robot bee built by Gunther Cox,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Robot_Bee.JPG

or two if we don’t change our ways. We can’t keep chewing everything up as soon as it sprouts a glimmer of life and expect anything to survive. Don't get me wrong, these "bees" are innovative and a good expression of the benefits which technology can bring in the face of today's problems, but they are no replacement for the real thing.

We’ve forgotten that we stand upon nature, are sustained by it, are a product of it. We seem to think that we can survive without the fundamentals of life that brought us into being, in global terms a mere flicker of time ago. Yes, probably in a mere twenty or thirty thousand years a new form of what once was will regrow itself (unless we successfully poison all life itself, which at one point I considered nigh-on impossible but now… we really might kill it all. Kill us all. Every bee, ever mouse, every flower, every bacterium, every mammal, every fish, every spark of life). But that’s not really a comforting thought for most people and in no way alleviates the terrible suffering of the only world we have.

But back to the bees. Just the bees.

Most people I have ever met think there are two kinds of bees. Sometimes three. Honey bees and bumblebees – and “killer bees”, which most people don’t know ARE honey bees, and something we ourselves brought to life and unleashed on the world. Even fewer people realize, in this cut-off, boxed-in world, that bees aren’t the only pollinators (some people remember butterflies…). Bees, to most modern concrete-dwellers are a fairybook animal, a creature with a stinger (often depicted at the wrong end) and a smile and a flower in one “hand”, a symbol for a double-edged sword but hardly anything we DEPEND on. And certainly not to be encouraged… why, some people are allergic to the stings, so they obviously have “no place” in our gardens – no, they “belong” in cultivated hives out where the kooky people who grow food live; they “belong” in the walled-off, tamed parklands (but not where people picnic!). We create gardens of plants foreign to the local pollinators, spray them with poisons, isolate them away from the Earth in pots and planters, and discourage diversity. We spray the bees themselves with poisons if they dare come close to our homes.

But enough about “humanity”. Let’s dig into my own small oasis. I was raised right, I was raised to understand the web that is sustainable life. How things are now is a source of agony to me.

I moved, 13+ years ago, into a Dutch single-family home with an unusually large garden for the area: it’s about 10 x 4 meters, a strip off the back of my house with an alleyway behind that used to be backed by a nearly-hundred-year-old juniper grove that someone deemed fit to slash out three years ago, leaving a pit of mud and stumps, scattering rare amphibians and a huge murmuring of starlings to the city’s foul winds and changing my view from peaceful singing mini-forest to just the back of some boring dilapidated row-house and the street on the other side. When I moved in here, the garden was a plain of graveled concrete tiles edged with some mostly non-native shrubberies. This would not do.

Without going into immense detail – because this post is about the bees, not the garden itself – I’ve spent the past 13+ years re-wilding it. I ripped out the concrete and planted a small lawn of hardy grasses which I have allowed to be infiltrated by dandelions and nigella. I bought native plants from the local eco-nursery and I picked seed-heads from poppies growing in alleyways to scatter in my garden. If a native plant volunteered, instead of shrieking about “weeds” I encouraged it, and now among other things my garden is awash in various wild geraniums. I allow sticks to rot, encouraged by thriving isopods, under the shrubs, and I delight in the spiders and wasps and the carpenter ants that neatly control the aphids for me. In the last few years there’s been a huge uptick out there of ladybugs, damselflies, ichneumonid wasps, crab spiders, you name it – and bees. So many bees.

Some like the sage best, others the dandelions, others the wild geraniums or the passionflowers or the borage or the buttercups or the St John's wort or the toadflax. And so on. And there are far, FAR more than two kinds.

For identification I use an international curated database of natural species, cross-referencing wherever possible, and I am confident in the identifications here down to at least a genus level, but in many cases don't know WHICH leafcutter or mining or sweat bee I've photographed, and would appreciate any input (and corrections) which anyone with more extensive personal knowledge can provide.

Without further ado, let’s break down the ones I’ve been able to get photos of. All of these were photographed right here in my own little strip of an urban garden.

Honey Bees

We’ll start with the Bee Everyone Knows, the honey bee. Incredible to think that this animal, present in droves on every continent but Antarctica, is a product of a human time far more healthy than our own, a time when we understood that we are a part of a larger world and worked with it rather than tried to pave it under and render it a mere skeleton of itself (a skeleton we are even now grinding to dust). Although there are several types of bee

which produce honey as we know it (eight that we have discovered), it is Apis mellifera, the Western Honey Bee, which our ancestors domesticated and spread to every part of the world. First domesticated before 2600 BC, they have become a symbol for all pollinators and shaped the very development of our species. Although they thrived in every environment across the whole world for millennia, now we are killing them. Our tendency to force things into concentrated areas and destroy the rest of the natural world means that even where they aren’t falling prey to poisoned air, water, and land they suffer from Colony Collapse Disorder and mite infestations, and have nowhere to go to escape. Thousands of years of one of the most amazing and successful symbioses of our history on this world and now we’re choosing to shit all over that and act like that’s OK, our “right”, even some kind of twisted imperative.

I am proud that in my garden I see dozens to hundreds of honey bees every day. There’s a botanical garden nearby with a few hives but most of these must be from wild hives, as bee cultivation in this close concretized suburban neighborhood is not really a thing. Nesting in brick piles and dead trees and under overpasses and in abandoned bits of waste ground, they are as threatened as anywhere but seem to be holding their own here – at least as long as my garden isn’t the ONLY refuge. I was delighted a couple of years ago when a swarm flew through the garden, thousands of bees all at once out of seemingly nowhere, all around me and then gone, off toward one of the parks. I hope they found a good place for the new colony, I hope that swarm is doing well.

Bumblebees

Next let’s have a look at bumblebees. Most people think that’s all there is to it – they’re bumblebees. One kind of bee, bumblebees. But that is far from the truth.

Unlike honey bees, bumblebees don’t create enduring colony-hives that span generation after generation. Each year, for most species, a Queen wakes from hibernation,

having overwintered somewhere safe (yet another reason to stop destroying everything natural and replacing it with cold hard artificial stone and glass) and seeks out a place to start a colony. I have, in hope, lined much of the garden out of sight under shrubs and deep in the lilies, etc., with large overturned terracotta pots, as these make excellent colony sites. I hope one will choose to settle with me one year. They’ve done so nearby, certainly – I see enough Queens to know they’re not far.

Once the Queen has chosen a site she wastes no time in setting up the nest in accordance with however that species does it: some seek out holes in walls or trees and create cells of egg chambers inside, others nest in shallow holes or even above ground and build their nests out of fibers or debris. Carder bees are so called because of the “combed” appearance of the natural fibers they collect to build a nest on the ground, usually in dense grass. As the colony grows, the bees forage by day and return

to the nest at night and then, as the seasons wane, they die off, in the end leaving only a young Queen who, having mated with the last males, seeks a place to safely overwinter. And the cycle begins again in spring. Here are the types of bumblebee which I have been able to welcome to my own garden:

Early Bumblebee

Bombus pratorum

One of the first to build nests each year - thus the name - these small (+/- 1.2 cm) bumblebees are the very picture of a "busy bee". They're very difficult to get pictures of because they zip so speedily from flower to flower, never choosing the one I got the camera focused on in advance. They nest so early - often in February - that there is even evidence that they can sometimes complete two full colonial cycles in one year if the second queen matures early enough to skip hibernation. In my garden they're particularly fond of the sage, teeming with a pleasant buzz all over the purple flowers. They nest above ground, often in old, abandoned bird nests.

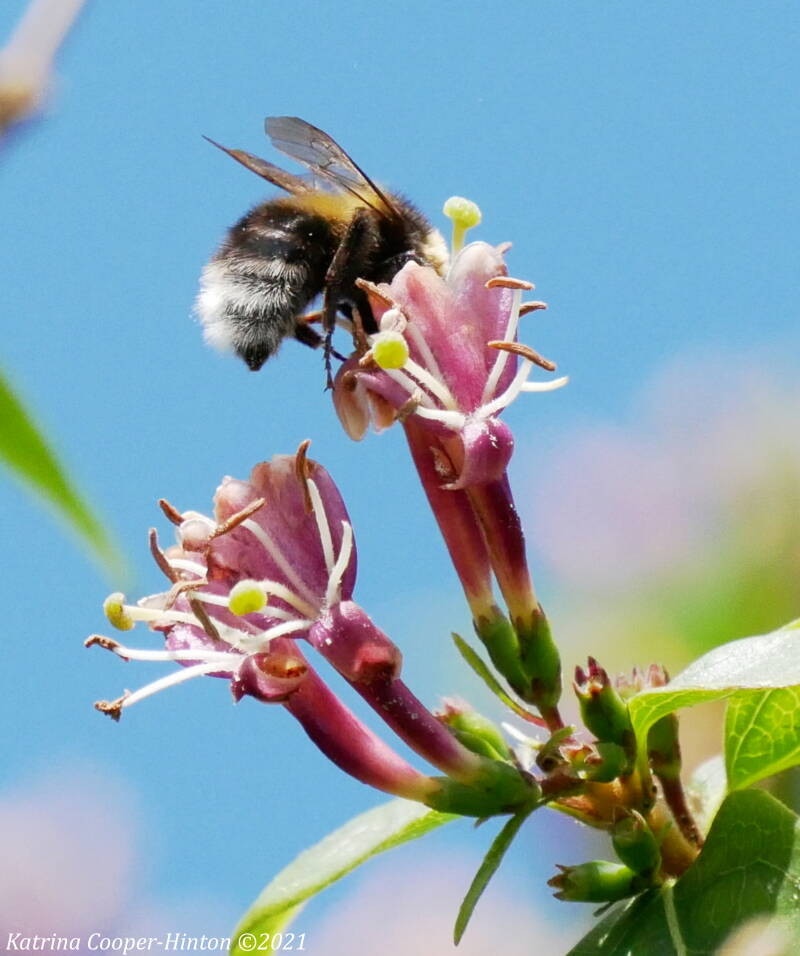

White Tailed Bumblebee

Bombus lucorum

The Queens of this species sometimes have to be taught that I am welcome in my own garden. Every couple of years one nests near enough by to decide I'm an intruder, and responds to my presence by zooming scarily directly at my face with her stinger brandished. I've found that simply by staring them down I can get them used to me (except that one particularly grumpy one that one year, who needed to be warned away sometimes with a waved piece of paper). These are the ones most likely to someday make use of my upside-down terracotta pots; I keep hoping! Large bees, the Queens are enormous - up to 2.2 cm - and they are avid forgers. They nest in hollows such as abandoned mouse nests or hollows in trees or stone walls, and colonies can reach more than 400 workers. The Queen layers wax egg cells with pollen inside the nests. In my garden, they particularly like the cotoneaster and passionflowers (that said, ALL the bees REALLY like the passionflowers).

Tree Bumblebee

Bombus hypnorum

Tree bumblebees often prefer habitats scorned by other bees, making them a particularly important pollinator as they "take up the slack" in a lot of areas. They regularly nest close to human habitations, founding colonies in hollow above-ground spaces such as disused bird boxes. In clement times they normally produce two colony cycles in a year, and Queens have been known to usurp existing colonies by killing the reigning Queen. They're quick and busy little bumblebees, less defensive/aggressive than many of the other types, and in my garden they're most attracted to the honeysuckle. Their colonies can reach between 150 and 400 workers.

Carder Bee

Bombus pascuorum

After choosing a site in a hollow such as a mouse nest or depression in the ground or clump of dense grass, these golden bumblebees collect grasses, moss, and other natural fibers to build their nests. They "comb" these into 2-cm balls, the walls reinforced with wax, and in each of these they include a 5-mm wax bowl of pollen and up to 15 eggs. The Queen will also make a 2-cm-tall wax bowl filled with nectar for her own use on lean days. After the eggs hatch, she never leaves the nest again, depending thereafter on her foraging offspring. The colony can reach a peak size of 60 - 150 workers and then quickly shrinks again until in the end, only a young (mated) Queen remains to emerge in spring and seek her own new colony site. The ones that visit my garden tend to spend a lot of time with the wild geraniums, but seem to have very broad tastes in general.

Garden bumblebee

Bombus hortorum

I don't know a lot about these guys; apparently I've been seeing them for some time, as they're the ones most likely to fly around with their extremely long tongue hanging out, but I didn't know that they weren't one or another of the other kinds because it's only in the past couple of years I've been skilled enough at getting close to them without interrupting their natural behavior, and they look quite a bit like some of the other types from a distance.

Research tells me they prefer grasslands, because they use dried moss and grass to build underground nests; we do have some small horse and cattle fields relatively nearby. They prefer deep flowers, and indeed in my garden seem most attracted to the honeysuckle and sage. The females only mate once, near the end of the colony's life, storing the males' sperm as they overwinter in hibernation.

Large Red Tailed Bumblebee

Bombus lapidarius

I don't see as many of these as some of the other kinds but they're far from infrequent visitors. They really like the borage in my garden, and the cotoneaster and dandelions. Reading up on them I learn that they tend to create loose, smaller colonies of up to 200 individuals, socially close (and therefor warm), and can range for more than a kilometer while foraging. They nest and forage at higher temperatures than most other bees, making them an extremely important pollinator as they can nest into hotter areas than others, and suffer less from extreme heat.

Buff Tailed Bumblebee

Bombus terrestris

I'm not going to say much about these bees as their size, behavior, range, and etc. are so extremely similar to the White Tailed Bumblebee (see above). This one is enjoying pollen and nectar from a passionflower, which although not native here seems to attract ALL the bees, ALL the time, when in bloom.

Other Bees

That there are other kinds of bees than the above seems lost on most people. In reality there are at least 20,000 species of bees. Of these, 250 are bumblebees, between 500 and 600 are stingless bees, 8 are honey bees, and the rest are solitary bees. I've been lucky enough to be visited regularly by the following:

Yellow-Face Bees

Hylaeus

Extremely common in my garden, these curious and engaging little bees will boldly try to drive even the largest bumblebees off of flowers they wish to make use of. They're very fast and hard to photograph. Nesting in dried twigs and other

detritus, they carry pollen in their crops instead of manually like most bees, and regurgitate it once back at the nest. A genus rather than a specific species, there are at least 20 kinds worldwide, and I do not know which this is.

Furrow Bees, Sweat Bees, Miner Bees

These extremely small and quick bees are tricky to photograph but I've been having some luck lately. They tend to zoom quickly around the sage and passionflower and wild geraniums, dive-bombing each other and other, much larger bees frequently. They're in the Megachile group - the Leafcutter Bees.

Furrow Bee

Lasioglossum species

I'm not sure which kind of Lasioglossum this one is. One of a broad group generally referred to as furrow or sweat bees, this kind tends to favor the ceanothus. I see quite a few of them.

Ashy Furrow Bee

Lasioglossum sexnotatum

As the above bee, these little guys, also members of the group referred to as furrow or sweat bees, also really like my ceanothus. I see a LOT of these tiny buddies.

Furrow Bee

Lasioglossum species

Another "some kind of furrow or sweat bee", these particular little fellows, of which I see quite a few, really like toadflax.

Common Sweat Bee

Lasioglossum calceatum

Most of these really little guys just love the toadflax, which is ubiquitous in my garden for most of the warmer months.

Orange-Legged Furrow Bee

Halictus rubicundus

These are nesting in tunnels they excavate under my lawn. The females create a ball of nectar and pollen, upon which they lay a single egg before sealing it into a brood chamber underground, digging deeper and deeper with each chamber to a depth of, often, 12 cm.

Gwynne's Mining Bee

Andrena bicolor

These bees also nest underground, up to a meter deep, but I don't know much more about them. This is to my knowledge the only one I have seen in my garden.

Furrow Bee

Lasioglossum species

Another in this same broad grouping, as far as I know this is the only one I've seen.

Metallic Mining Bee

Lasioglossum (Dialictus)

Not a specific species but a category, these usually metallic bees nest in tunnels or under tree bark. I see quite a few of them.

Leafcutter Bees

Patchwork Leafcutter Bee

Megachile centuncularis

Nesting in hollow spaces such as dried stems, holes in walls, and the like, these bees (as all leafcutter bees) use their jaws to cut off parts of leaves which they carry to the nest, roll up, and fill with pollen and a single egg. Once they've filled the nest hollow they seal the entrance with several discs of leaf material and wax. Here are the other leafcutter bees I have seen in my garden:

I don't know what KIND of Megachile (leafcutter) bee this is but it's quite a bit smaller than the Patchwork above.

As with the one above, I don't know the specific species, but this kind - of which I see quite a few - is very small.

And last but far from least, another small fuzzy Megachile bee on my borage.

Hereby concludes the tour of the bees of my garden. I hope you've enjoyed it. If I find a "new" kind I promise to excitedly update this blog.

If you would like to see my whole collection of bee photos, please visit the album "Bees" at this link:

https://somerandomchick.picfair.com/albums/208651-bees

Add comment

Comments